An Enquiry: On What Lies Between

Exploring connectedness, connectivity & connectorship

Photo credit: Sam Baumber

Hannah Smith, November 6th, 2020

We are so used to looking at objects. We look, and we see things. People, trees, birds and bees. My organisation and your organisation. Discrete items — each one apart from another. But what if — instead of separation — we saw connection? What if we could see what lies between? The glue that holds it all together. Our families, our organisations, our communities — and our ambitions to make the world a safer, kinder, fairer place.

These Covid times have got more of us thinking about the importance of connection, connectedness and connectivity. What it means to feel connected, disconnected, more connected. About how we develop and maintain our connectedness without physical proximity. The importance of our connection to the rest of the natural world. Like never before, we are experiencing just how interconnected our personal and global challenges are. There is a brighter light shining on the stickiness between us. The glue between ourselves.

Imagine if we could talk as easily about this ‘invisible in-between’ as we do about the ‘things’. Had a similar depth of understanding around how this mysterious matter grows and develops. And a similar appreciation for the craft of fostering, nurturing and developing it. Perhaps a little more fluency, a little more dexterity here could enable us to better connect our multitude of individual efforts. Perhaps it could help us invest and design more wisely. And perhaps it could even increase our collective capacity to address the hyper-connected challenges of our hyper-connected world.

Photo credit: Hannah Smith

Connectedness, connectivity & connectorship

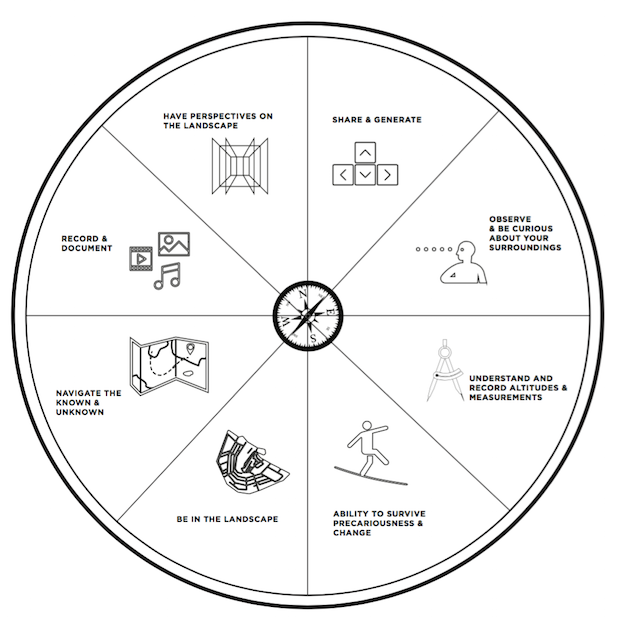

Biologist Merlin Sheldrake calls the relationship between organisms ‘the most basic principle of ecology’. I am embarking on an enquiry that centres on this principle — that there is value in developing our capacities to see, understand and work with ‘what lies between’. It’s an enquiry with three strands — like a woven braid. Each strand a part of hauling ourselves forward in a quest to see better through the lens of connection.

The first strand is ‘connectedness’. What is mysterious matter, this glue, this stickiness, this amorphous substance that grows between us? We reach for words like trust, empathy, familiarity, intimacy but how exactly does it emerge and evolve? What conditions facilitate or inhibit its development? What’s the difference between ‘a connection’ and ‘connectedness? And why does it matter?

The second strand is ‘connectivity’. Think of this as the amount and quality of connectedness in a system. The mycelial network from which our shared endeavours grow. How do we assess the presence, volume and quality of connectedness across our systems? And how purposefully are we fostering it? Is it, in fact, something that can be fostered or will serendipity and magic always play a role?

Which leads to the final strand — ‘connectorship’. The idea that there exists a craft, a skill, a practice — of actively developing connectedness and connectivity. Like entrepreneurship — it’s an activity that seeks to create new value in the world. Whereas entrepreneurs grow ventures, businesses and organisations — ‘connectors’ grow connectedness between nodes in a system — thus fostering its connectivity.

Photo credit: Hannah Smith

Unravelling the strands

“Relationships move at the speed of trust, and social change moves at the speed of relationships” — Jennifer Bailey

Let us begin with connectedness. Imagine it as a substance. Something slightly sticky perhaps. It attaches us to each other. To our organisations. To our places. It is largely invisible and variable in its consistency but — like pancake batter or a good sourdough — it’s a substance we can get to know with practice. Think of all the language and knowledge we have for objects, for places and for people. And compare that with the paucity of our ability to visualise, describe and understand the quality of what attaches them to each other. To me, this is where the juice is — in the joining.

I am curious as to the extent to which this substance, this ‘stickiness’ can be understood in and of itself. Is what lies between two people, the same as what lies between a person and an organisation or community? Or between a person and place? Does connectedness develop in the same way between humans, as it does between a human and an animal, or a place? And if so, what might we learn from this? What might be the implications for our thinking about relationships between humans and the rest of the natural world?

Photos credit: Sam Baumber

“The future won’t be a new big, tower of power- but well trodden paths from house to house” — Raimon Panikkar

And so to connectivity. When I think of connectivity I picture a rich, colourful, dynamic heat map. Something that helps us perceive and understand more about the quantity and quality of connectedness in a system. Not just the connections — the simple ties of ‘who knows who’ that you might see on a classic network map — but an indication of the nature and state of the relationships between the nodes. Where the most generative pockets are, and where there are gaping holes.

Connectivity as the soil — the earthy goodness — of a system is another useful metaphor. Where it is rich and well nourished, what is seeded there is more likely to flourish. Paying attention to how and where connectedness is forming — or failing to form — can help us understand more about the health of our systems. About what’s flowing and growing, and about where the blockages are. In turn this can help us focus our energy and resources. What kind of conditions and activities help or hinder greater, and richer connectivity? And where it is poor, how can it best be nourished?

“Hope is the consequence of action” — Cornel West and Roberto Unger

Which brings us to connectorship. If connectivity is the soil of a system, perhaps those who do the work of making and deepening connections are the quiet wee creatures of that system — the birds, the bees and the beasties. As there appear to be natural entrepreneurs, so there seem to be natural connectors. Most of us know people who seem to more frequently facilitate connections between others. They are often quiet, humble, more introverted types. Focused on the whole, not the parts — and who instinctively understand the value of enhancing connectivity.

So much is written and understood about the science and art of entrepreneurship. It is studied, funded, supported, held up as an economic engine and a pillar of strength. The entrepreneur is seen as an alchemist — a spinner of gold from rare reserves of ideas, energy and dogged determination. Imagine if connectorship occupied a similar place in our consciousness. ‘Connectors’ as the weavers of all the untapped potential hidden between people and organisations. With the same commitment to purpose, but through nourishing whole systems instead of single organisations. What skills, tools and insights might ‘connectors’ have that all of us can learn from? How might we better resource the valuable work they do? What might be possible if we could become more conscious, purposeful and skilful about how we nourish our connectedness, and the connectivity in our systems? How much more effective could we become?

Where to from here?

On one level, connecting is something we do and understand intuitively. An in-built human capacity — much like parenting, caring, grieving or falling in love. But I believe it’s still possible to interrogate our instincts. Embrace our curiosity and refuse to rest comfortably on easy assumptions. As these strange times continue, it is surely valuable to be continually enquiring.

Kāore te tōtara e tū mokemoke — The majestic tōtara doesn’t stand alone

It’s easy to look at the forest of our endeavours and be drawn to the biggest, most striking trees. But these trees are rooted in soil. Kept healthy by a multitude of quiet creatures. For those of us more accustomed to a paradigm of separation, this more interconnected, whole systems perspective can be daunting. After all, heroes make for compelling stories. But I believe it’s time for such narratives to shift. Our interconnected challenges call for interconnected solutions. We humans are not separate from the earth, the water and many forms of life on which our own lives depend. We exist in relationship. A great wild, occasionally overwhelming mesh of relationship. This knowledge lies at the heart of so many indigenous cultures, yet has been sidelined by our increasingly dominant Western ways of being and doing. The times we are living are surely telling us it’s time for a re-understanding. In the words of poet William Stafford, ‘it is time for the heroes to all go home’.

Over these coming months I will be purposefully enquiring into these notions of connectedness, connectivity and connectorship. Combining thinking and doing, scholarship and stories I will explore some dimensions of connectedness, the challenges of building connectivity and consider the skills and tools of connectorship.

My grounding place for this work will be Aotearoa New Zealand, through my work with Pocketknife and as part of the Edmund Hillary Fellowship — a fascinating, global collective of bright minds and warm souls who are engaged in meeting the challenges of our time head-on. By experimenting, exploring, creating and reflecting — together — I hope we can build connectivity in our own systems, and share learnings along the way. Please connect or comment if you have thoughts, questions or would like to get involved in the exploration. Or sign up for regular updates here.

And more soon. Much more.

Naku te rourou, nau te rourou ka ora ai te iwi

— With your basket and my basket, the people will thrive

Thanks: Many, many conversations have helped shape this piece and this project. Particular thanks to Sam Baumber, Natasha Zimmerman, Hélène Malandain, Richard Alderson, Erin Crampton, Denise Young, Rosie Walford, Ants Cabraal and my dear friends at The Point People — whose time, words, wisdom and encouragement have made all the difference.

Why the feminine business principles?

Jul 13 ·

This is the first of three posts sharing about a collective investigation with The Point People into what sisterhood — or regenerative—economics might mean. The second is here, and third here.

This questioning began a number of years ago for me, when I came across the Feminine Business Principles created by an artist & business person in LA, Jennifer Armbrust co-creator of sister.is. For me, the principles are a way to experiment with reaching a new level of business in the world — to start to define what regenerative business might look like.

They are important because we can see it is impossible to regenerate the earth if you operate an extractive business model. If we want a shift to regenerative farming and to regenerate the earth and all beings, then we need to have the way businesses operate also be regenerative.

These principles are so vital to me because they give me hope that business can transform into a force for positive change.

They are literally the backbone of how I operate in the business world, they give me space for all the things that many people said had no place in business. Even just the first principle, ‘you have a body’ — in the business context is oddly profound. How did business get so disconnected from being alive?

In May Cat Drew and I led the first exploratory workshop on Sisterhood Economics for our monthly The Point People meeting. To get people thinking about Sisterhood Economics (which has no definition) we shared a bit about what economics means and is for, and some of the questions we might ask ourselves to imagine this new economic paradigm.

It’s important to acknowledge the economy is a concept humanity constructed to support our civilisation, it is a social science not a natural science. The word economy derives from the greek words for ‘household’ and ‘manage’. It’s literally how we want to manage households.

A given economy ‘is the result of a set of processes that involves its culture, values, education, technological evolution, history, social organisation, political structure and legal systems, as well as its geography, natural resource endowment, and ecology, as main factors. These factors give context, content, and set the conditions and parameters in which an economy functions. In other words, the economic domain is a social domain of human practices and transactions. It does not stand alone.’

The economy is not a set structure we must exist within but something we can help to transform by the way we organise, the way we produce, use and manage our resources.

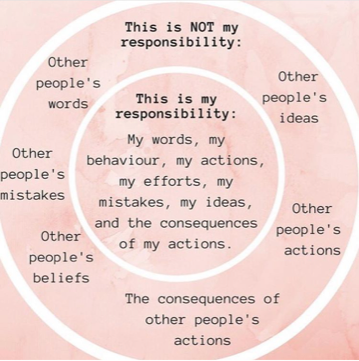

Sisterhood economics is about recognising this and beginning to construct a vision of an economy that supports many feminine values, as outlined by the contrasting diagrams of the values of the feminine economy and masculine economy from sister.is. Consider that the current economy we have built acts to reward those who are willing to win at all costs; to foster aggressive competition; to reward those who already have assets; to keep us all in a state of feeling we need more; to hide our real selves at work; to aspire to have more than others and grow bigger than others; and ultimately to make as much financial profit as possible. Is that what we want?

Can you imagine a world where your work is a healing for yourself and others? Where telling the truth is rewarded more highly than turning a profit? Where feelings are celebrated and seen as a vital part of a thriving economy? Where you feel you are enough, just as you are? Have you ever experienced that in your life, or seen that in others? Can you recount a story, or give an example of what that looked like? If you are having difficulty just take a moment to realise what that means, how deeply it is engrained in us that we must participate to win, to accumulate assets for ourselves, to be better than all those around us and to always feel we aren’t enough. Is that what life is for?

As part of the workshop we asked ourselves the following key questions and shared examples and thoughts about beginning to answer them (they are rather massive questions, this is the tip of the iceberg).

What are the myths of the current economic paradigm? In her book Donut Economics Kate Raworth shows that the concept of ‘trickle down economics’, or that inequality will even itself out, is a story based on extremely limited data. Despite the limited hypothesis, this concept somehow become economic fact and was taught to all economics students for 50 years. It is of course a very compelling story for politicians and the wealthy as it means they don’t have to worry about inequality as the economy grows, so maybe no wonder it was so quickly adopted. Raworth lays out in her book how this principle has now been shown to be a myth — even Simon Kuznets who originally published the hypothesis re-iterated that it should not be used for making “unwarranted dogmatic generalisations”. And yet, our stories about how the economy works still haven’t changed. Read more here and we definitely recommend reading Donught Economics to uncover many more economic ideas you might be surprised aren’t true.

How can we have an economy that encourages capital sequestration rather than capital evaporation? Molly Madden of Red Hen Collective first introduced us to the idea of capital sequestration and capital evaporation. Capital sequestration is the idea of keeping capital embedded in the community, so a dollar spent in your local bakery will have way more impact on people’s lives than a dollar spent on Amazon that immediately evaporates into an off-shore bank account, and is traded on stock markets, having almost zero impact on the community. Essentially, how can we have an economy that is about nurturing a community, rather than ‘nurturing’ abstract figures that benefit a few people? A good example of focusing on capital sequestration is the Cleveland or Preston model of community wealth building, where spending money on local businesses is built into how the local council (and all its procurement systems) work.

If scaling and growth is not the goal? What are we doing this for? What might business look like without scaling up? If they don’t grow every year? I shared that when I look deep inside myself I realise it’s very difficult to imagine a positive existence where I was to live day to day without any concept of progress or change. I think that is true of most humans I know, we have to believe we are working towards something. However, I certainly can imagine a world where what I was working towards was not growing the company, scaling up and generating more profit. We discussed that there are many ways of scaling up impact without growing a company (more on that in the next question). What if we decided we had enough profit and instead we were working towards more gratitude, more ease, more empathy, being more fully self-expressed, being more connected to nature?

If you aren’t scaling up then you don’t get ‘economies of scale’. Where have you seen examples of infrastructures building resilience in fragmented systems?

It feels like this question speaks directly to a lot of the work The Point People do. Here are a few examples that occurred to us right away:

The work fellow Point Person, Cassie Robinson, is doing with Catalyst to massively accelerate UK civil society’s use of digital is a great example of infrastructure that is building resilience for the many different charities, institutions and entities that make up civil society today by providing digital know-how in a collective way. And the Foundation Design Lab is bringing many ideas and ways of working from the design world to the same sector to further build capacity across the many different smaller entities.

Small Food Bakery in Nottingham set up the Small Food Collective to provide supportive tools for the many local shopkeepers and food producers in their city. The Small Food Collective call to action for their first meeting was “There are many mechanisms (production and retail) that need to be re-examined, there will be many solutions, and perhaps all of them are useful. But underpinning everything, a better approach has to be one where power is devolved into the hands of more people, in stronger local networks. Our city needs more food producers and shopkeepers who are prepared to step outside the status quo and work in the interests of building a new cuisine with ingredients traceable back to good people and healthy soil. That’s why we need to mobilise a Small Food Collective.”

Farming the Future is an example of funders working in this way, they are specifically providing funding to support collaborations between different regenerative food and farming charities, businesses, influencers etc as well as building a general comms fund focused on collectively harvesting and sharing messages of a more regenerative food system far and wide, for the benefit of all involved. The power of these collective projects and messages are usually inaccessible to smaller fragmented groups, so Farming the Future is providing a new level of resilience for the many diverse smaller entities.

If the economy is a tool to support civilisation: What is our economy designed for? What do we want our economic system to support?

This feels like one of the most important questions of our day if we see the economy as the way we will continue to navigate life on earth and really the context for this whole exploration into Sisterhood Economics. In some ways this is the realm of the brilliant economic thinkers who are questioning and proposing viable visions for the future of our economy, such as Kate Raworth and Marianne Mazzucato (read more here). It is also a question we can all ask ourselves on a day-to-day basis through the lens of Sisterhood Economics, starting with the first feminine business principle, how have you recognised your body today in your work? Imagine — a new economics as the recognition that you have a body. Radical right?

In the next two blog posts first we explore some examples of Sisterhood Economics in action and then we re-imagine what the economy would look like if Sisterhood Economics was the norm.

Reimagining the economy with Sisterhood principles

Jul 13 ·

This is the third of three blogs that Abby and I have written to record the collective thoughts of The Point People about a new type of economy we see emerging, which we’re calling sisterhood economics, inspired by Jennifer Armbrust’s The Sisterhood. In the first blog, Abby talks about why we think this is important. In the second, we share the examples of what we think these businesses look like. And this piece reflects the thought activity we did to reimagine what the economy would look like if sisterhood values were the norm.

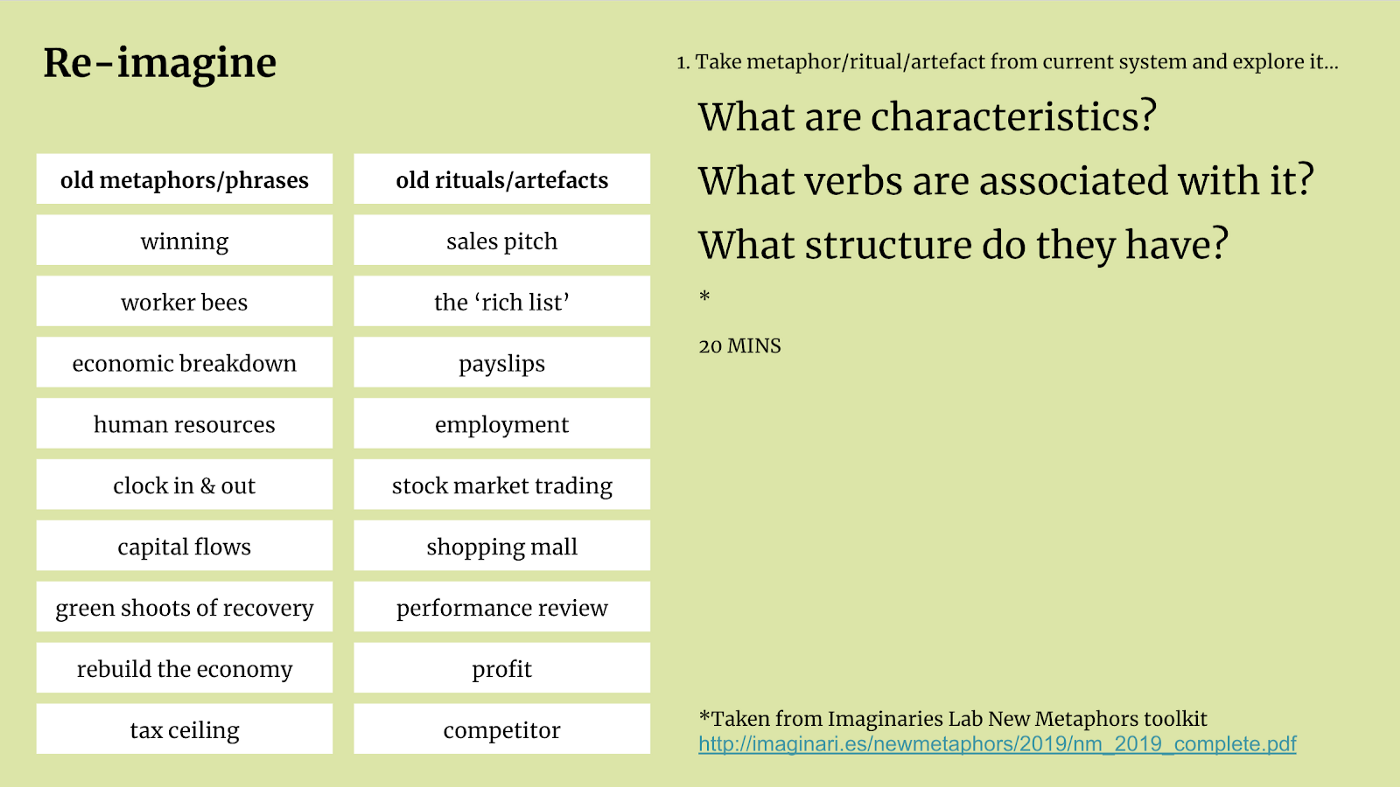

Inspired by Dan Lockton’s New Metaphors, we spent some time first exploring the current metaphors that frame how we see (in the West) the economy: the words and phrases we use, the rituals, the values. Sometimes these are so ingrained in our language, we are not conscious of them. Lakoff and Johnson’s seminal Metaphors we Live By (1980) revealed how embedded these are in everyday language and govern how we see the world (and therefore our capacity to reimagine it). For example the metaphor ‘argument is war’ positions an argument as a tense act between two opponents (“his criticisms were on target”, “he shot down my argument”), rather than a joint dialogue exploring an issue.

Then we took one of the new Feminist Business principles, and did the same: unpacking it and understanding the words, patterns and structures associated with it. The final step was to take one of the old rituals or artefacts (e.g. the rich list, a pay slip, a performance review) and apply the new principle to it.

Here is where we got to…

Slide explaining our first exercise

Old metaphors…

Unpacking metaphors we currently use to expose how we frame our thinking

Upwards growth. Words like ‘build back better’ and ‘recovery’ suppose that the economy has weakened or crumbled and needs to grow. And the idea that we have to bring back what was before rather than something new. Some of the words and metaphors we use around ‘building’ that are ‘concrete’ and immovable, and others like ‘green shoots of recovery’ that have more organic connotations.

Two-way, hierarchical, binary power relationships. There are many words and phrases which denote exchange or transaction, but are two-way and with no sense of interdependence. ‘Profit and loss’, ‘winners and losers’, ‘queen bee versus worker bee’. These are binary camps you can’t fall between.

Within a performance review, someone is assessing someone else rather than it being a collective reflection. Employment means that someone is in the employ of someone else. The payslip on the one hand provides stability and legitimacy (and acts as a certificate). But it also is an arbitrary value someone else places on you (and bears no relationship to the actual value you have created that month), and places the receiver in a passive position of power (as opposed to issuing an invoice).

Dehumanised descriptions of resources (so that we can exploit them). ‘Human resources’ — or even the acronym ‘HR’, are actually living, breathing individuals with personalities, and the ‘environment’ which literally means surroundings, is also a living, breathing planet with an abundance of animals and plants living together with us.

Aggressive behaviours. The ‘rich list’ is the epitome of home economicus. It’s about ranking, striving, dominating and winning, and in a very one-dimensional way all about money. The idea of the list is a hierarchical rank with everyone better or worse than someone else. There are scarce resources at the top, so people need to compete. Words like ‘undercut’, ‘dog eat dog’, ‘sales pitch’, ‘be the best’, ‘rich list’.

Slide explaining our second exercise

New metaphors

Exploring new metaphors to help reframe what economy could be through different lenses

Reciprocity and flow. Which still allows exchange and market, but something that feels a fairer balance of power. We’re not just transacting with businesses in a commercial sense, but were able to integrate with business missions in other ways? Or not just transacting with nature but integrating with it.

Osmosis, porous, weave/woven, interdependence. We feel that our time is more engaged across different work — or purpose — boundaries (and not just paid work or purpose) rather than tied to a single 9–5 job.

Part of nature. Rather than us being simply connected to it, or it being an ‘externality’. Rather to talk about the planet as ‘the body’, and consider that how you treat your body will have an impact on the world. In Maori language ‘I am the land and the land is me’ is one metaphor by which they start and frame their conversations.

Balance and optimisation. We have to live within the limit of what we can regenerate. We don’t just want profit or loss, but something in between. Rather than a focus on maximisation, we should move to optimisation: just enough to satisfy needs rather than being a bit ‘grabby’.

New artefacts and rituals

Applying new framings to existing artefacts and rituals to make tangible what we mean and translate it into concepts people can understand

Payslip. Wouldn’t just be a certificate or proof of how much you’ve been paid in a transactional way, but could be a moment of giving thanks and acknowledging value. If work is around being in a relationship with other people to create some value, you are bonded to them through that creation, and it could be celebrated as a monthly moment of collective achievement.

Balanced budget. Delicate and skilled dance between the minimum resources a business needs for the wellbeing of the world, and what it gives back.

Paying a bill. Not just paying money in return for a commercial product/service/offer, but other ways that you could transact (for example giving your time, skills, connections, something from your garden etc).

The rich list. Rather than reading ‘rich’ as monetary, we could see it as the ample or bounteous stories that come through the act of doing (of providing something that gives people joy, or helps them achieve something) rather than the result of profit. And these could be surfaced through storytelling (where the listener also attributes the value they see), rather than a one-dimensional measure of value.

To end, Abby read an extract from Emergent Strategy by Adrienne Maree Brown

“If the goal was to increase the love rather than winning or dominating a constant opponent, I think we could imagine liberation from constant oppression. We would suddenly be seeing everything we do, everyone we meet, not through the tactical eyes of war, but eyes of love. We would see there is no such thing as a blank canvas, an empty land or a new idea, but everywhere there is complex, ancient, fertile ground full of potential. We would organise with the perspective that there is wisdom and experience and amazing story in the communities we love and instead of starting with new idea or organisation all the time, we would want to listen, support, collaborate and merge and grow through fusion not competition. We would understand that the strength of our movement is the strength of our relationships which could only be measured by their depths. Scaling up would mean going deeper, being more vulnerable, and being more empathetic.”

Signals of what a Sisterhood Economy looks like

Jul 13 ·

This year, The Point People has been holding a loose enquiry into a new type of economics. Inspired by Jennifer Armbrust’s The Sisterhood, and their feminist business principles, we’ve been delving into what a regenerative, caring, generous business model might look like. Far away from the race to the top, the eyes on the prize (pound sign) and limitless growth. It was suggested at a collective gathering in January, and on the verge of Government decisions of how to support businesses to go forward after the immediate shock of COVID is subsiding, it feels more necessary than ever. So as well as weekly The Point People sense-making and support calls during COVID, we’ve been exploring how energy within businesses can be channeled into something that can nurture (rather than extract from) ourselves and the planet. In this first blog, Abby sets out why they matter to her personally, and why she felt like The Point People should hold this conversation.

Part of systemic design (another enquiry we’re holding with Design Council), is about seeking out signals of the future now, and designing ways of bringing them together into a bigger whole (or a ‘glowing constellation’ as Cassie Robinson calls it), and showing this to the world so others can be inspired and join. So in that spirit, our first task (after checking with which of the feminist business principles resonated with us personally) was to share an example of a business that displayed them — translating abstract principles into tangible examples. The following is a list of them, with some tensions we see described at the bottom. As this is still an early exploration we broadened our thinking beyond just the business world, to draw from different initiatives working in this way — what is interesting about all of them is that care seems to be at their core. Then the next blog shows how we have unpacked metaphors around the current economic system, reimagined them, and translated them back into what new artefacts, rituals and systems could be…

The values:

In the wine world, the wine producers produce the wine and harbour most of the risk but don’t get paid for 18 months which is extremely challenging for cash-flow. So Red Hen set out to pay the vineyards first, or on exchange of goods, or even prior to exchange of good. This allows the producers to have more flexibility so they can invest in more regenerative, environmental practices. What the Red Hen Collective didn’t forsee is that this one change — paying the vineyard first — has meant they had to reconsider the whole business model because the whole wine distribution system is based on paying the vineyards last, that the vineyards must take on the risk. If the producers are to be paid first then that risk must be taken on by others, and no one is willing to take it all on. It must be distributed through the system or navigated through more direct relationships with the people who are going to drink the wine.

Small Food Bakery

Small Food Bakery sell bread built on a completely different value system of nourishing every-being involved in that bread’s life, including the soil — they have completely different definitions of success. They offer alternative forms of exchange inviting customers to ‘barter with us, food is currency’. They also work with all players in the food system to build strong relationships and networks that allow for a new level of efficiency and nimbleness, supporting farmers who are using more ecological farming practices not just by buying their wheat but also creating menus that reflect the many different crops they produce and sharing the stories with customers. You can hear Kimberly Bell of Small Food Bakery talk more about her approach to redefining business in this episode of Farmerama.

Mercato Metro

The principles on which its founded are all about circular economy, interdependence, but also care and empathy and ease. For example, there are lots of people in the local community that are entitled to free school meals, so the owner made it really easy and natural for them to get those meals from the market, meaning it is really serving people living nearby. They also have a strong apprenticeship and experimentation approach, building skills and providing a springboard for local businesses.

Code for COVID

A network of 1,000 coders who gave their time, knowledge and experise for COVID related challenges. It was generative and generous.

First Things First 2020

An updated version of the 1960 manifesto, this online commitment brought designers together and commit to a set of social design values. The power of the many gave the manifesto credibilty and reach, as they then went out into the many businesses and professions they were part of to spread these principles further. A flock initiative.

Is a fashion centred research plan which aims to shift language and practice within fashion from growth logic to earth logic. Started by two professors, one from fashion and the other from design, it aims to bring together a series of researcch and experiements to transform the fashion industry.

Birdsong

An ethical fashion brand which has honesty as a core value. There is no photoshop. There is transparency about their incentives and their supply chain. In an industry where this is so competitive, they’re trying to be responsible and socially driven.

London Early Years Foundation

The London Early Years Foundation could be described as the Buurtzorg of the nursery sector. They invest in low income areas and cross subsidise from high income areas. They talk about purpose and how care is intrinsic to later success. An orgainsation that makes care valued.

Little Village

Founded by one of our fellow Point People (Sophia Parker), it has feminist principles. It is generous in that it is about recycling good quality children’s clothes and toys to those who are struggling to afford them, and generative in that it also builds community by bringing people together across social and economic divides in a way that builds empathy. And through its volunteering programme it creates opportunities for people, including parents Little Village has supported, to grow new skills and networks. For Little Village, success is not measured by how far or fast it can scale the model, but instead in the long term by an end to child poverty, and in the more immediate term, by a shift in attitudes and beliefs about the causes of poverty.

As we discussed these examples, a number of questions and potential tensions came to us:

Feminine economy and language. We discussed that the words on the Feminine Economy diagram above felt potentially too tame but maybe words like fierce and warrior aren’t right either. So, what are new words for this economy? We explore some of these in our next post.

Resistance to growth. Feminist economy businesses don’t need to scale. For example, Little Village sees an ambition to scale as problematic: would it reinforce and prop up a system that has failed children for many years, by providing a sticking plaster over the ever-widening chasm of inequality? By framing its work as an intervention to shift the system, it keeps the focus on its work of building community, growing empathy and shifting unhelpful stereotypes. However this approach doesn’t always reflect the mindsets of investment models that equate success predominantly with scale and growth in more traditional terms.

Some of the B-Corps don’t fit. Overall the companies are socially minded, and can be really generative (for example hosting or sparking other organisations). But from what we know, some of the leadership styles don’t fit (often because of what is being asked of them by investors — see below).

Values versus behaviour. We know the behaviours of many women that we personally know in business innovation circles speak to all these qualities, but the language of start ups are about the standard structure of competition: growth, touching millions of people and scale. This is clearly a tension.

The Navigator —Responses to a disrupted world

May 4th, 2020

Part 3: Perception

This series — The Navigator — is reconciling how The Point People are navigating this moment of collective grief and uncertainty, the transition from a pre-Covid time to an uncertain future. It is an imperfect record of our experiences and reflections over this period.

Afew weeks further into it all, and our virtual gatherings continue. In various constellations, but always with a similar orientation towards care and exploration. We speak of phases, momentum, beginning to think forwards to a time when we might re-emerge — blinking — into the light again.

For some of us it’s brought to mind the Kübler-Ross Change Curve — how it feels to be at the bottom of the rising limb, beginning an uncertain climb. Our individual curves take different forms — perhaps one day we’ll draw them — when we can see all this with a little more perspective.

Perspective and perception — themes that seem to come up a lot in our conversations. A couple of weeks ago, one of us experienced a long, fast drive for the first time in a while — the clouds and the landscape zipping by. After so much containment it was discombobulating this sense of speed and space.

It makes us wonder if our sensory landscapes might be changing with the shrinkage of our day-to-day, not to mention all the screen time. Screens allow for seeing and hearing, but our other means of sense-making are truncated. How does this affect how we then experience the ‘real’ world? Away from the screens, is there a little more awe? A little more ecstasy? A little more awareness of the intense delights of full sensory engagement?

Question: What are you perceiving anew?

Perhaps this is what also lies behind our changing relationship with place. We barely even noticed the layers of place in our lives before. We were comfortably multiple— it was home and work and cafes and trains and planes and parks and cultural venues and so much more. Newly confined to just one place, we began by grieving those we’d left behind — but more and more we are finding ways to enjoy and celebrate where we find ourselves.

We are better acquainted with how the sun tracks across a kitchen table as the hours go by. The dimensions of our homes are expanding as we discover new ways to arrange ourselves; unique corners for work, rest and play. When the end of a street becomes a place to go to celebrate a birthday, we know we are discovering the richness of place like never before.

For now, all these personal micro-worlds are separate — perhaps we’ll never truly know another’s. But a macro-experience is being shared like never before. Whoever we speak to, wherever they are — we are all facing new realms of stretch and challenge.

It helps us appreciate how far care travels. We may not be sharing touch or presence, but it seems we’re pro-actively caring for each other more than ever. We newly understand that to care is to act. It is something that we do. And we are all doing so much care. The calls, the messages, the bouquets, the birthday surprises. Innumerable nuggets of thoughtfulness. If our To Do lists were relabelled To Care lists, how much prouder we would be of all we are achieving just now?

Question: What does it feel like to prioritise care over achievement?

The Kindness Rocks Project, Wellington. Photo credit: Hannah Smith

Asthe days of this time pass, increasingly we find ourselves asking — where to from here? How will we all emerge into the afterwards? There is anguish, anger and fear around deepening social inequalities — Sophia’s perspective from the frontline is a sobering one. Yet at the same time, we are each feeling chinks of optimism around what these vast new volumes of ‘lived experience’ might be doing for our capacities for empathy and imagination:

“We won’t forget that it’s possible for the supermarket shelves to suddenly be empty — this is a defining moment for years to come. Things won’t just go back to how they were before this, the question is what will this ‘new normal’ look like? What do we even want it to look like?” — Abby

There is something intoxicating about this challenging time being a harbinger of a new era. In the words of Rebecca Solnit “…disaster is a lot like a revolution when it comes to disruption and improvisation, to new roles and an unnerving or exhilarating sense that now anything is possible”. An emboldening perspective for sure but practically speaking, it’s still hard to think forward. To frame our thinking we lean towards a few broad brushstrokes of scenario planning — i) a return to ‘normal’ ii) a state of permanent emergency or iii) a society built on a new social contract. It feels clunky and incomplete, but it’s what we have for now.

Question: What tactics can we use for thinking about ‘afterwards’?

And so we keep going. We keep on paddling and we take the days as they come. He waka eke noa — we’re all in this (canoe) together.

‘Til next time,

The Point People x

Compiled by Hannah Smith. With a special shout out to Victoria Stoyanova and her new venture, The Institute of Belonging.

Contributors: Sneh Jani-Patel, Abby Rose, Cathy Runciman, Nish Dewan, Beatrice Pembroke, Sophia Parker, Ella Saltmarshe, Anna Mouser, Eleanor Ford, Jennie McShannon, Sarah Douglas, Jennie Winhall, Cat Drew, Victoria Stoyanova, Kyra Maya Phillips & Joana Casaca Lemos.

The Navigator —Responses to a disrupted world

Apr 20th, 2020

Part 2: Oscillation

This series — The Navigator — is reconciling how The Point People are navigating this moment of collective grief and uncertainty, the transition from a pre-Covid time to a brave new world. It is an imperfect record of our experiences and reflections over this period. We are all grappling, recalibrating, coming to terms with something new and discombobulating. There is so much to navigate — practicalities, possibilities, hopes, thoughts and fears. We hold no answers, but we travel these unknown seas together.

Photo credit: Sam Baumber

Afew weeks on, further into this new time. Our Point People calls remain a lodestar for many of us and they are ever warmer. For most of us the call takes place in the evening, following the new normal of Thursday night cheers for the NHS, for those who are at the coal face of it all. For one of us, it is morning. Bleary eyed as the day begins, there is comfort in sharing the evening of the day before. We are all separated these days, what’s a few thousand miles between friends?

Our conversations swerve and curve. Rolling between personal, cerebral, practical, emotional. From dancing like plants, to the challenges of post-pandemic urban planning. The oscillation suits us, seems to suit the mood of this time as we each find ourselves rocking between so much of everything. In fact it seems this oscillation is one of the few constants we are finding in this strange new normal.

Grappling, juggling, see-sawing, lurching — words we use often as we navigate these new seas. Noticing this I wonder — are we in fact finding ways to be more comfortably plural with thoughts and feelings of ‘both at once’? We are grieving AND we are optimistic. It happened so fast AND the days seem so slow. We are swept up in concerns for society and humanity AND dealing with deeply personal challenges. We are being forced to face our edges, on both sides, at once. There is a mass recalibration going on. We are working out how to be and do in an entirely new context. No wonder it feels hard.

There is a sense of everything being in sharper relief. This ‘great pause’ is endowing us with heightened sensitivities. Perhaps it is the confinement, the concentration. Typically modern humans, many of us have lives usually spread across multiple places, multiple roles. We are jugglers and plate spinners — seeking and trying and racing all the time. And now we must stop for a while. It’s making us question our places, our roles, our priorities. We are holding the sadness of all we can’t have, whilst encountering untold beauty in this strange new confinement.

Kyra describes her experience below:

Medieval monks, I heard recently, believed that the world was a book, and that moments of transcendence — what I imagine Virginia Woolf would have called “moments of being” — are those rare, wholly ecstatic, and sublime flashes of light that allow us to read a few lines before it all goes dark once again.

It is often said now that the world — our book, if we continue with this monastic train of thought — has indeed gone dark (“I hope you are well during these dark and uncertain times,” reads one e-mail; “The lights have come off,” offers a headline). It is as if humanity is experiencing a prolonged total eclipse — “the sun,” as Annie Dillard wrote in her stunning 1982 account of an eclipse, “was going, and the world was wrong.”

Photo by Jongsun Lee on Unsplash

The world being wrong is a sentiment I am, at the best of times, completely overwhelmed by. The irresolvable tension between the sublime and the everyday gnaws away at my soul, often leading to tortured admonishments that tell me how little I know of how to live a good life, or how impossible it is to derive meaning from daily existence. These extraordinary moments, when you can read those few, sacred lines, when the world comes alive and you can feel the life quivering inside it, are — so much of the time — inaccessible to me. The words of Lily Briscoe, from Woolf’s To the Lighthouse, often circle around in my mind:

“To want and not to have, sent all up her body a hardness, a hollowness, a strain. And then to want and not to have — to want and want — how that wrung the heart, and wrung it again and again!”

I am aware of how easy, or cliched, it is to say that I will now hold dear all that this radical suspension of normal life has exposed as meaningful, but that before was veiled by the numbing effects of habit. But this, precisely, is what I am now holding in my heart: some of the most melancholy moments of this tragic time happen when, like in a vivid dream, what has been lost appears (it is right there!) and yet you cannot reach for it. Our friends are in front of us, two metres away, perhaps, while they drop off a batch of homemade pasta, or a loaf of freshly baked bread, or, even, a glorious pile of books, and yet we are unable to touch them.

The impossibility of fulfilling our deeply held longing for those tiny, ordinary, daily intimacies — even, perhaps especially, with strangers — is one of the many losses that illuminates the inseparability of dailiness from the ecstatic. They are not, as I was utterly convinced they were, opposing forces. There is always, it feels right now, a quality of the sublime — that longed for “moment of being,” when the world is a book you can read — in the everyday.

Yes, the world is a different, and in so many desperately tragic ways, a darker place than it was only a couple of months ago. But as with everything, there is a crack — and through it, the light gets in, enough of it, even, so that we can read what this moment might be trying to tell us.

Photo credit: Sam Baumber

The light is getting in right now. The air is clearer; we can see differently. It may be tricky to see far — mostly it feels like there’s just yesterday, today and tomorrow. But where we can, we soak up these moments of quivering, radiant life.

To end, some beautiful words from John O’Donohue, read by Fergal Keane; they really are worth a listen.

Until next time, take good care.

The Point People x

Compiled by Hannah Smith, with writing by Kyra Maya Phillips. For more from Kyra, subscribe to Marginalia, a beautiful newsletter made for The Point People.

Contributors: Sneh Jani-Patel, Abby Rose, Cathy Runciman, Nish Dewan, Beatrice Pembroke, Sophia Parker, Ella Saltmarshe, Anna Mouser, Eleanor Ford, Jennie McShannon, Sarah Douglas, Jennie Winhall, Cat Drew, Victoria Stoyanova, Kyra Maya Phillips & Joana Casaca Lemos.

The Navigator —Responses to a disrupted world

Hannah Smith

April 9th 2020

These days are challenging in so many ways. We are coming to terms with a new normal. This is not what we thought 2020 would bring and yet here we find ourselves. As The Point People we feel drawn to respond.

The Point People are a close collective of friends and collaborators, who have long found each others’ hearts and minds a tonic. We share an interest in systems thinking, and bring perspectives from diverse professional and personal lives. In these strange days we have found turning to each other nourishing and helpful — and want to share our noticings, learnings and reflections.

This series — The Navigator — will reconcile how we are navigating this moment of collective grief and uncertainty, the transition from a pre-Covid world to a more physically distanced existence and into an unknown future. It will be a record of The Point People’s experiences and reflections over this period. We will share authorship, publish irregularly and allow the content to evolve as our experience does.

We are all grappling, recalibrating, coming to terms with something new and discombobulating. There is so much to navigate — practicalities, possibilities, hopes, thoughts and fears. We hold no answers, but we travel these unknown seas together.

Part 1: Beginning

As the strange new world began to unfold, The Point People network was buzzing with thoughts and noticings. Instinctively it seems, we were drawn to the hopeful things — to sharing and collating what we were hearing and seeing; examples of ways that resources, energy and behaviours were transforming in this unfamiliar time. We were also drawn to connecting more frequently.

In a shared document we asked each other:

What’s an insight you’ve found helpful/something you have observed recently that is helping you navigate everything?

What small acts of kindness/ ingenious workarounds have you seen that you’d like to share/amplify?

What are the new behaviours/dynamics that you’re seeing?

What’s supporting you to be well?

What questions are you asking? (about the crisis or society?)

From our conversations so far, and some of the responses to the questions above, here are some initial reflections and a few themes we’ve noticed emerging. We’ll share more as we go.

Time

Many of us have spoken and shared a new awareness of, a new relationship with time — how ‘time feels weird’ just now. We’ve observed how things seem to be taking twice as long, even though many of the ways we usually spend our time are no longer possible. On our calls we’ve discussed the challenge of ‘unended, unboundaried time’ and shared anxiety about failing to maintain our usual levels of production, contribution and commitment. We share a sense of navigating a new time continuum — seeking to be more deliberate in trying to stay present, and endeavouring to avoid projecting into the future.

Question: What are we learning from this new sense of time?

Fixed Versus Flux

The design thinkers amongst us have been particularly struck by the human ability to innovate, and adapt to unexpected constraints. Whether individuals working remotely, businesses shifting their organisational production to what is needed most or neighbours finding ways to become more connected. It’s all happened so quickly, yet people have been able to respond fully and well. Rapid pivots in business models and innovative collaborations have emerged — like catering companies becoming home delivery services, or fashion labels moving to production of masks and gowns.

We see the importance of keeping resource flowing in a system, as areas of slack and of need rapidly evolve — empty hotels housing key workers, breweries repurposing their production processes to make antibacterial hand gel, people contributing time to mutual aid societies. Much of this is occurring organically through the insight and kindness of individuals reacting to what’s happening. Even in our own system, we see an evolution — we are moving away from fixed modes of interaction and rigid expectations to a more malleable approach — leaning into where capacity exists, and understanding that everything is shifting, all the time, for all of us.

Question: How can we better attune to flows of resource through a system? How can we work with these flows to better support those who are struggling?

Care and Generosity

More generally, we see how COVID-19 is forcing many of us to see more systemically — focusing on relationships and interdependence. Several of us feel we’ve never communicated so much — more regular connection with family and friends and so much purposeful reconnection and kindness. Every day there are new initiatives that seek simply to provide sustenance, care, love — with the expectation of nothing in return. From teddy bears in windows to enliven family walks, to online art, language, dance classes, museum tours — there is a sense of generosity and mutuality. We are offering more to our fellow humans, finding ourselves friendlier, less hurried in our everyday interactions — it feels like we’re being softer somehow.

The Point People are also reminding each other to go gently — to take time to ease into this entirely new, extremely challenging period of our lives. If we don’t write, produce, learn, create, do all the time, it’s OK. If we feel overwhelmed or bewildered sometimes, it’s OK. We are reminding each other that we don’t need to have all the answers — compassion, kindness and ‘threads of love here and there’ might just be enough for a while.

Question: What are we learning about care?

On that note, more soon. Expect some thoughts on what we’re learning about place, complexity and emergence. ’Til then, stay safe.

The Point People x

Photo credit: Hannah Smith

Chapter compiled by Hannah Smith.

Contributors: Sneh Jani-Patel, Abby Rose, Cathy Runciman, Nish Dewan, Beatrice Pembroke, Sophia Parker, Ella Saltmarshe, Anna Mouser, Eleanor Ford, Jennie McShannon, Sarah Douglas, Jennie Winhall, Cat Drew, Victoria Stoyanova, Kyra Maya Phillips & Joana Casaca Lemos.

Systemic design: examples of evolving and current practice

At the beginning of December, The Point People together with the Design Council hosted an event on systemic design. We had 120 people sign up in less than 24 hours and a large waitlist. There is interest and intrigue. What is systemic design and why is it important?

This is a long read and like the event, full of rich information which we try and distil down at points throughout.

I start with an intro to why we convened the event and why design is good at working in systems.

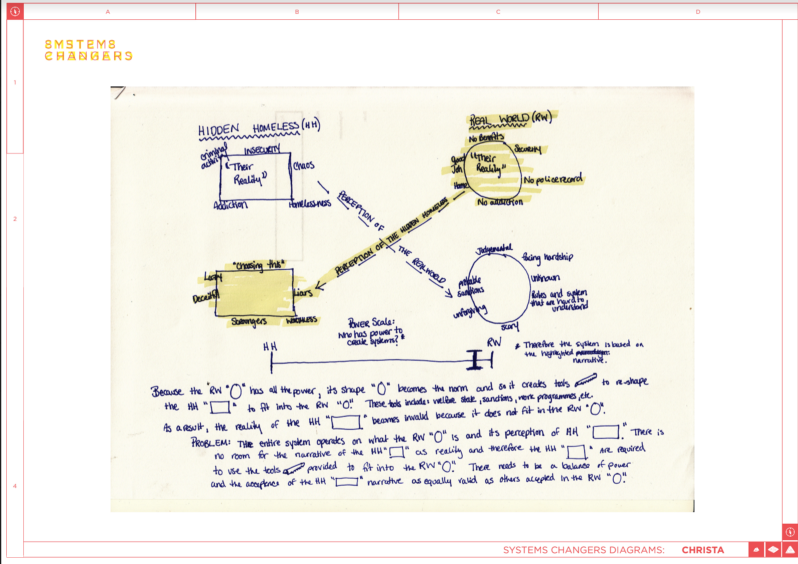

Jennie Winhall talks about designing for a new system: inversing patterns, developing new norms and connecting a community of change, giving employment as an example

Cassie Robinson writes about transitioning to a new system: building the field, creating new narratives and creating clusters of what a new field could look like, from her work with the Catalyst (which supports the civic sector adapt to a new world)

Alistair Parvin, Ilishio Lovejoy and Nick Stanhope provide three talks to highlight elements of systemic design: finding the root of the problem, providing information as feedback and knowing your role, from their experiences in planning, fashion and children’s services

Introduction and why we convened the event.

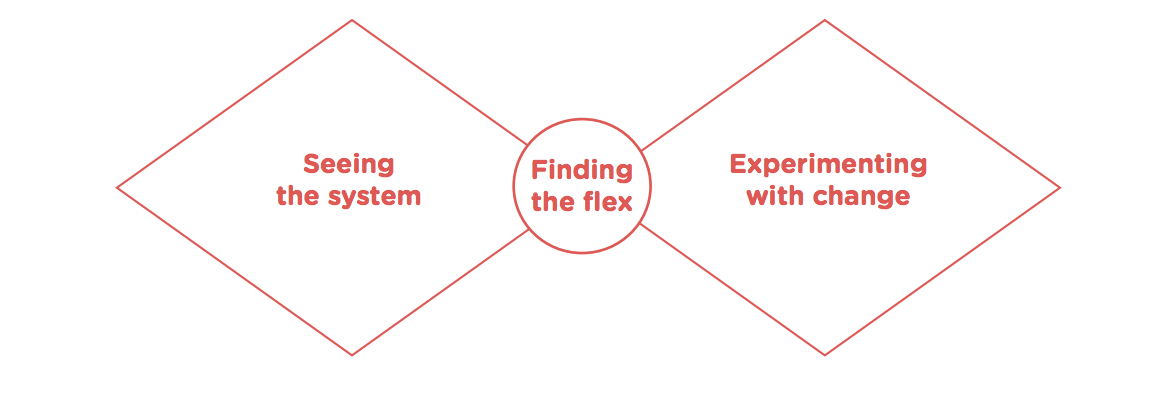

There are a few definitions and writings around about systemic design, design for systems, systems transformation, transition design etc. But if we start with what we’re trying to address… The issues that we are facing at the moment are complex, messy and interconnected. We need to dig deep to find the root causes, which can be things that are said, and unsaid — like unequal power or the way we think about an issue. There is no one fix. Things are interconnected, so we do one thing over here and it pops up over there. And sometimes we need to design a new system entirely rather than just patching up or improving the current one.

We believe that design can hold some of the answers here. And people in the systems change world have increasingly been using design methods in order to bring about desired change.

But this is an emerging practice. It might be simply the intersection between design and systems theory. But it might be something a bit different. So we are conducting a loose enquiry into how this has and is evolving — and doing this by listening to designers who have been working systemically. And because we know people are interested in working in this way, we are sharing this as we go. We can’t entirely define it right now, but we can share some elements. And we want to do this so that designers can explain to their colleagues/clients what it is, start working in this way, and therefore develop their own practices to add into the mix, influenced by other designers or other professions too.

We started off by saying that designers work in systems already. Systems are made up of different elements that are connected together. A system can be biological (forest), social (a neighbourhood), organisational (the health system) or technological (air traffic control or a computer system).

Some aspects of design means that it lends itself well to working with complex systems:

Synthesis — whether it is designing a house, an engine or a public service, design is a task of discovering how elements can come together into a coherent whole that is greater than the sum of its parts.

Reflexivity — designers discover how to move forward with a design problem by making a move (drawing something, modelling something, taking a new action), seeing how that move then changes the situation and using that new understanding of both problem and opportunity to make the next move. It is reflection in action: what Donald Schön calls ‘back-talk’ between the situation and the designer.

Creation — designing is also about the act of bringing something new into being: sensing the potential and then realising it. This matters to system innovation because it is one way in which we understand not just how things are but how things could be. And because design is visual, we can also paint a picture of what is possible, so that others can see its potential too.

Designing for a new system: inversing patterns, developing new norms and connecting a community of change

Jennie Winhall spoke about how to design for a new system (rather than making improvements within the current system). She says that when it comes to social systems, a new system forms through a change in one or more of four things: purpose, power, relationships and resources.

She gave examples of three different approaches to changing systems:

Inversing the pattern: At Participle, they wanted to create a 21st century welfare system. In order to do this, they looked at common patterns of activity across public services. Most deliver a service, rather than supporting people to help themselves. They work with individuals rather than with family units. They are limited to public finance rather than the resources inherent in relationships and communities. This adds up to a welfare system that is burdened by demand, rather than strengthened by participation. All of these services display the same dysfunctional patterns because they are based on the same underlying system logic: the same system ‘principles’ underpin each service. By flipping these principles around, Participle was able to design new employment, ageing and health services across the country that demonstrated a very different welfare system — in which people create their own solutions.

Changing dominant norms: At the Rockwool Foundation, they created Nextwork, a new employment system which connects young people and companies together in networks that build young people’s working identity. It takes a very different approach to the current job centre system. One of the challenges of introducing a new approach into the very dominant norms of an existing operating system is that the system has what Rowan Conway calls a kind of immune response: it rejects the new activity. To be successful the staff have to be highly skilled in navigating between the old and the new. That meant the design team scaling up the system nationally had to develop new ‘transitional’ tools. First they created a service blueprint showing staff how the new service works and trained them on delivering it. But it was a disaster — people couldn’t understand the purpose behind their new actions. So they threw away the blueprint. Instead they worked with theatre techniques to train staff in improvisation based on three core system principles. This has been much more successful: staff understand the purpose of acting in a new way, operate from a different set of core beliefs and are confident in developing further activities based on those three principles. This principle-based approach is a way to change the mindsets, behaviours and norms of dominant systems.

Connecting together a new ecosystem of innovation: ALT/Now, with the RSA and Mastercard’s Centre for Inclusive Growth have designed a programme to develop a new safety-net for 21st century work. Our current system of unemployment benefits, employer-delivered training, pension contributions and unions doesn’t work in a future increasingly made up of people in flexible, independent work, moving from employer to employer, or gig to gig. So we need to redraw this landscape. The team brought together a cohort of entrepreneurs to create a new system of innovations to support people working in today’s gig economy. One innovation alone is not going to change the whole system, you need lots of interventions — new ways of brokering jobs, smoothing income, new insurance models, new types of unions and new models for ongoing learning. These discrete innovations can have much greater power if they see themselves as part of the new ecosystem: they can amplify each others’ efforts and define a new market that benefits them all. The success of each venture depends on the success of the emerging system. Several ventures have already collaborated to form a safety-net for workers in the care sector. That’s the power of process of collective creation — and bringing them together into a community of change.

Transitioning to a new system: building the field, creating new narratives and creating clusters of what a new field could look like

Cassie Robinson spoke about her experience of designing the The Catalyst — which was originally set up as a way of building the digital capabilities for 40,000 charities and civil society organisation, but is now working to support the sector as a whole to continually adapt, become more accountable to communities and work together better for those it serves. It is operating at three different levels simultaneously drawing on the Berkana Two Loop Model and is funded by a mixture of Government and philanthropic funding.

Illustration by Cassie Robinson, model from the Berkana Institute.

Field-building

The first area of work that the Catalyst is undertaking is field-building and demonstrating early value in the overall concept. The activities happening here are responding to the sector’s immediate needs and through ensuring some of Catalyst’s initial activity happens in the present frame, they’re able to build goodwill and legitimacy. The work includes things like Open Backlog, a mechanism to reduce duplication of effort across the sector and encourage reuse, and the development of patterns and standards that enable and fast track more common approaches and shared infrastructure going forward. This part of Catalyts’s work is being done with a range of partners, who are funded through Catalyst. There are currently 30 different projects underway, all using Catalyst assets to visibly mark themselves as being part of the Catalyst transition work.

Visuals to show different elements of the Catalyst work

Networks and narratives

The second area of work that Catalyst is doing is a range of activities linked to networks and narratives. Another part of building goodwill and legitimacy is to shine a light on other people and organisations that are doing work that aligns with Catalyst’s mission. Deepening the network, connecting more of the system to itself and bringing coherence to it helps the ecology of people and organisations feel part of something that’s bigger than any of them individually. This is being done through commissioning content from the wider network and setting up a Catalyst “News Room” which Catalyst projects also use to create and share content. Alongside this, Catalyst projects are published on Ochre, a bespoke platform that shows the status of all the work that’s happening across Catalyst’s 30 (and growing) projects — an important part of transition work is to reflect the system back to itself, sharing progress, doing collective sensemaking and demonstrating momentum. This view of the system (held by someone in a ‘field-building’ role) means that different dynamics are revealed, and gaps and opportunities are made visible. It also requires an ongoing orchestration of connecting micro narratives (of the projects) with the macro narrative (of the whole of Catalyst’s ambition and mission).

The other aspect of this work is what Cassie calls “systems readiness” — using the sensemaking and intelligence being gathered across all of the Catalyst’s projects to understand what conditions need creating for the new system to emerge — a renewed civil society. In Catalyst’s case this has initially meant understanding what relationship dynamics need changing, what policies, regulation and decision making mechanisms are no longer fit for purpose, and the different ways that resources and value need to flow.

Redrawing the boundaries so a new system can emerge

If the field-building work was happening in isolation, and the narrative and network function was also only focussed on mapping and making visible the present, then Catalyst would simply be optimising the existing system (civil society). In this third area of work Catalyst is using a model called Clusters, which focus on the potential and creation of the future rather than the problems of what needs fixing in the present. Each Cluster (there are initially 8 across the UK) has been formed with the intent to explore the possibility space, making strong demonstrations and designing organisations to be in new relationships with each other, for example bringing together civil society organisations who would not normally work together, but who are trying to deliver similar outcomes in a particular place, or around a similar function (e.g. helplines) or to reimagine a particular service (e.g. childrens care). Here the narrative work shows how by drawing new boundaries around collections of organisations reframes the purpose of the system.

Alistair Parvin, Ilishio Lovejoy and Nick Stanhope at the panel discussion

Three talks to highlight elements of systemic design: finding the root of the problem, providing information as feedback and knowing your role

Alastair Parvin’s leads an organisation called Open Systems Lab. He spoke about their mission to change the planning system. He argued that all systems have an operating model. They can be quite clear, (like postcodes or grid references), but sometimes more opaque (like time or our historical understanding of land rights). But you can’t change a system unless you find it, and disrupt it. He likens it to ‘following the white rabbit down the hole’. He showed his maps of the system, starting at the relationship between rising house prices and the undersupply of homes, and then expanding out to increasing debt or lack of investment in construction innovation. So far, so normal (the top left image below). But then he flipped the map on its axis and looked at how lots of these causes and effects were all based on similar social values, knowledge models and methods of production. Such as manual paper based design methods, the way we think about money or — in red in the bottom left image below — freehold land ownership. You can then see how this underlying issue connects to so many elements of the system. So if you change that…you impact on many of the causes and effects.

Alistair Parvin’s system maps showing wide causes and effects, and the deep root cause that links them all

Ilishio Lovejoy is a policy manager for Fashion Revolution. In the fashion industry, one could argue that design is part of the problem — designers are designing clothes for a fast-fashion, consumer market which has a harmful impact on workers’ wellbeing in developing countries and environmental sustainability. Fashion Revolution was set up to challenge that. One of their main campaigns is the Transparency Index, providing more information to consumers about which retailers are more ethical, as well as campaigns where clothes have large tags to show the provenance of their manufacture. They have designed a number of different initiatives, using different levers for change, and inspire or work with others as part of a movement, including Spindye (which removes the environmentally damaging dying process) or Rent the Runway (shifting behaviours away from owning and towards renting clothes).

Fashion Revolution’s I Made Your Clothes campaign

Nick Stanhope is the Chief Executive of Shift, which is a service and product innovation charity working a lot around children’s services. He talked about the need for everyone to find their own role. He described a common situation where many charities, and design agencies who support charities, are in effect competing with each other for funding to provide services that help support their own mission. Which means that the incentive is for everyone to ‘talk up’ their own work as the most important (and trying to get more of it), rather than seeing their work as a piece of a larger whole that needs to exist alongside other initiatives, which will also require funding. Working in this way — as an innovation ecosystem or as a set of field catalysts mentioned by Jennie and Cassie earlier — also requires building relationships and making connections between organisations. This ‘invisible’ connective tissue needs designing. And a change of mindset, so that we don’t individually think we can ‘move a system’, but that we are ‘in service of a system’. He called for us to all be clear about our ‘role’ in the system, to be clear about the contribution we make, but how we have to work alongside others.

There are so many types of practice and elements to what they are doing, and there are different ways and words for describing what they are doing. But if we had to summarise the rich tips and discussions, we would say — that in order to design for today’s big challenges, designers need to:

Design deeply — Understand the wider context in which a person or idea sits, tackling the root cause of an issue — which might be things that are said or not said, patterns of behaviour or mindsets that frame the way we see opportunities.

Design hopefully — Imagine entirely new systems, and creating a clear narrative or vision that allows lots of people to design things that move us towards it.

Design disruptively — Creating something (and it can be small) that changes a behaviour, an interaction or a relationship — for example a new norm or a piece of information — and that can have a wider ripple effect.

Design collaboratively — Bring together a portfolio of innovations at different places across the system, and connecting to others striving for the same goal, working intentionally as an ecosystem rather than alone, with each knowing how to play their right role.

We hope the event inspired designers to consider how they can shift their practice to design more systemically — deeply, collaboratively, hopefully and disruptively. And to experiment with other methods (reaching out to other professions) and add to these practices. Please get in touch to share your work with us as we continue our enquiry.

The role of design in complex social and environmental challenges

Back in 2017 the Point People (Jennie & I) met with the Design Council to talk about co-hosting some events that linked together systems change practice with design practice. Two years later, and with the arrival of their new Chief Design Officer, Cat Drew (and fellow point person), they’re happening.

The purpose of these events is to raise the profile and understanding of what design can bring to the complex and systemic nature of society’s biggest challenges. These challenges — the climate crisis, the power of big tech, ageing populations, in-work poverty, and the polarisation of society — are not ones that anyone can tackle alone, and not ones that all the current answers aligned together would successfully address. We need to design for whole new approaches, for transitions from old frames into new, and to take a more systemic approach.

The community of people working more systemically has grown over the last decade, often drawing on design practice as part of this work. And there are more designers looking to bring a systemic approach to their design practice. We’re a group of designers who were early to bring a more systemic approach to our work, recognising the limits of service design back in 2010 when we set up the Point People, and we’re now keen to do several things -

Further explore and articulate the particular role design can play in transitions and systems change work, revisiting, revising and evolving some of the tools and practices we’ve created over the last decade.

Support more designers to adopt and evolve the practices, and show designers the unique role they can play in addressing complex social challenges.

And make the case to commissioners and funders to adopt systemic, transitional and design-led approaches.

This first workshop will focus on the particular role design can play, and we aim to leave the session with a set of principles or standards that describe this.

We’ll also be running workshops and events for designers new to working in this field, funders, and commissioners.

If you’re a designer, and want to get involved, please get in touch.

Collective Points

June’s Sensemaking: Regenerative Thinking

“The city of Leonia refashions itself every day: every morning the people wake between fresh sheets, wash with just-unwrapped cakes of soap, wear brand-new clothing, take from the latest model refrigerator still unopened tins, listening to the last-minute jingles from the most up-to-date radio. On the sidewalks, encased in spotless plastic bags, the remains of yesterday’s Leonia await the garbage truck. Not only squeezed tubes of toothpaste, blown-out light bulbs, newspapers, containers, wrappings, but also boilers, encyclopedias, pianos, porcelain dinner services.

It is not so much by the things that each day are manufactured, sold, bought, that you can measure Leonia’s opulence, but rather by the things that each day are thrown out to make room for the new.”

Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities

Like Leonia, we are living in a world built on ‘degenerative design principles’ — where we take the earth’s natural resources, turn them into stuff we use, sometimes just once, and then throw away when we’re bored or have moved on to the next thing we want. We’re caught up in a consumerist mindset where we are defined by our shopping basket, our taste in home décor, or our ability to keep up with the latest trends in fashion. A satisfied consumer is a fearful spectre, posing the threat of not buying anything, and therefore undermining the goal of continuous growth that was normalised in the last half of the 20th century.

In a world where ‘more’ is synonymous with ‘better’, cutting back on consumption and living in line with the planet’s resources can only really be understood as ‘lack’; or ‘going without’. It creates a sense of paralysis as each of us try to calculate what we might be willing to give up versus what we feel we’re still owed. I was talking to someone the other day who argued that it was fine for them to fly because they’ve cut out meat and dairy this year. What’s difficult though, is that the underlying mindset — that consumption is still the most desirable way of life — hasn’t changed.

Regeneration, which was the theme of our Point People gathering this month, offers the prospect of a different way of engaging with the world, with the potential to lift us out of the fear and paralysis so many of us are currently experiencing. We talked about ‘regenerative thinking’ as a mindset that has the potential to shape our individual choices and collective lives in radically new ways.

Kate Raworth has written about the seductive attraction of ‘growth’ as a metaphor for progress, that is deeply embedded in the Western psyche. To replace such a powerful frame requires us to find an equally compelling metaphor that has all the positive associations of growth, but that enables us to see the crucial importance of all the other elements of life and nature, beyond markets, that help us, and the planet, to thrive.

Regeneration and regenerative thinking could be just that frame. Regenerative thinking is built on a view that rather than humans being a virus on the planet, we have the capacity within us to regenerate the world. What feels important about ‘regeneration’ is that it has many of the positive characteristics of the ‘economic growth’ frame that has had so much power over the years. Both create a sense of forward momentum, of progress. And regeneration is fundamentally an imaginative concept, full of hope and the possibility of new life. It’s about joy, communion, connection and shared goals.

There were two themes in particular that we explored together.

Grounding our work

Here, our conversation landed on the question of what regeneration looks like in relation to our own practices at the Point People. Is consultancy inherently extractive? Can you be and act regeneratively without having some kind of more grounded connection to the land? What if we put our systems approaches into practice in order to advance our agenda? What would the Point People intentional community look like? We reflected on the power of the Bauhaus motto — ‘Hands On and Minds On’, based on the insight that we can’t think without doing, and that the two need to be deeply woven together for the richest and most powerful ideas. (incidentally I was reading the Peter Kalmus book noted below this week, where he talked about hands, minds and hearts — I think there is something very powerful in this).